Chapter 19 Moral

Realism Connects to Theism

We come, at last, as promised, to making

the case for theism.

But, in order to bring all the threads of my case together, I must first

go back and carefully review some assumptions that are implicit in this

argument, as they are in any argument based on Science.

What are we committing to if we agree with the points presented so far?

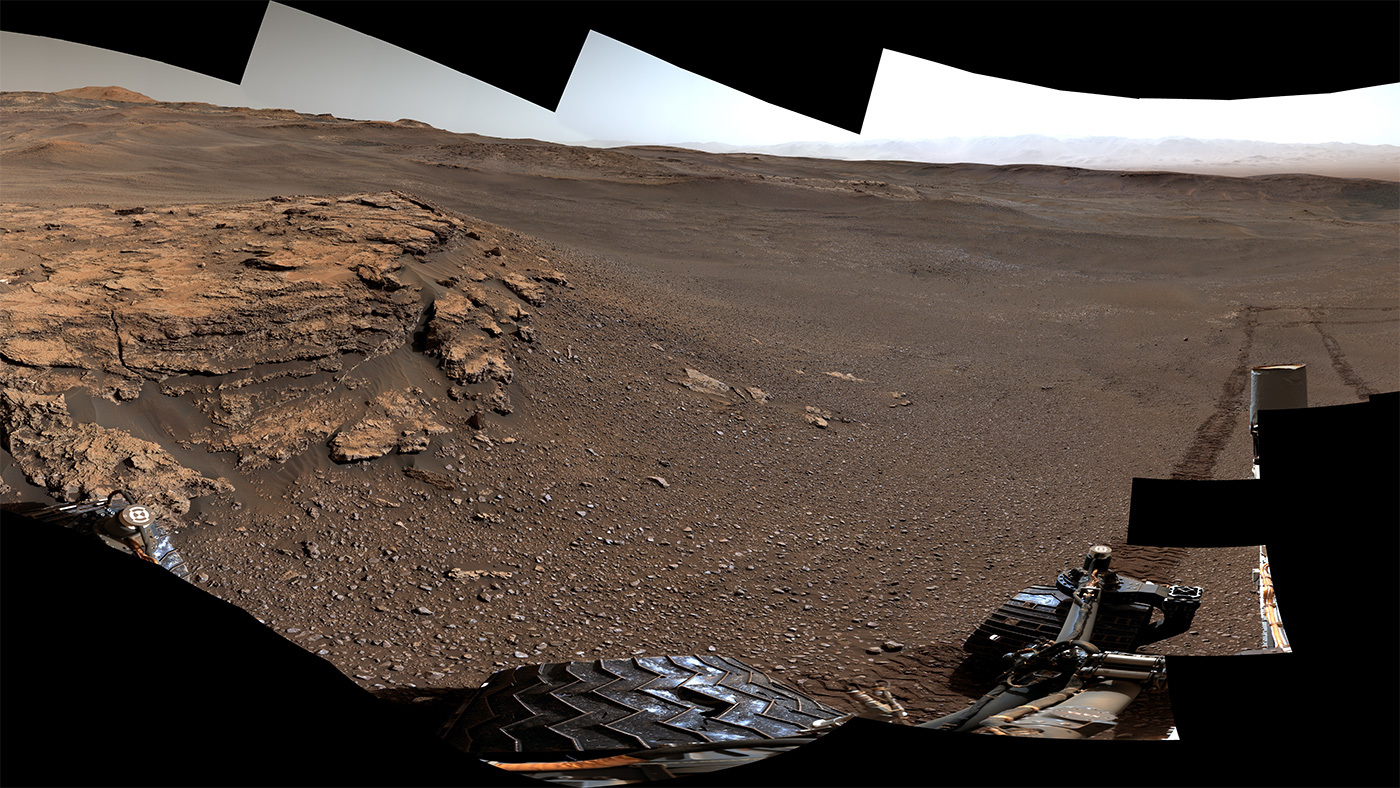

(When will

humans walk this landscape?)

Afternoon on Mars (photo by the NASA probe, Spirit Rover)

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

For many modern thinkers, an implicit assumption they are not conscious

of, and do not examine, is that the universe is a single, integrated system.

Every one of its parts connects to all of its other parts, and it runs by one

set of laws, each law consistent with all the others. We don’t fully understand

the system of natural laws yet. For example, we don’t yet understand how

sub-atomic forces and electro-magnetism relate to gravity. But in Science, we implicitly

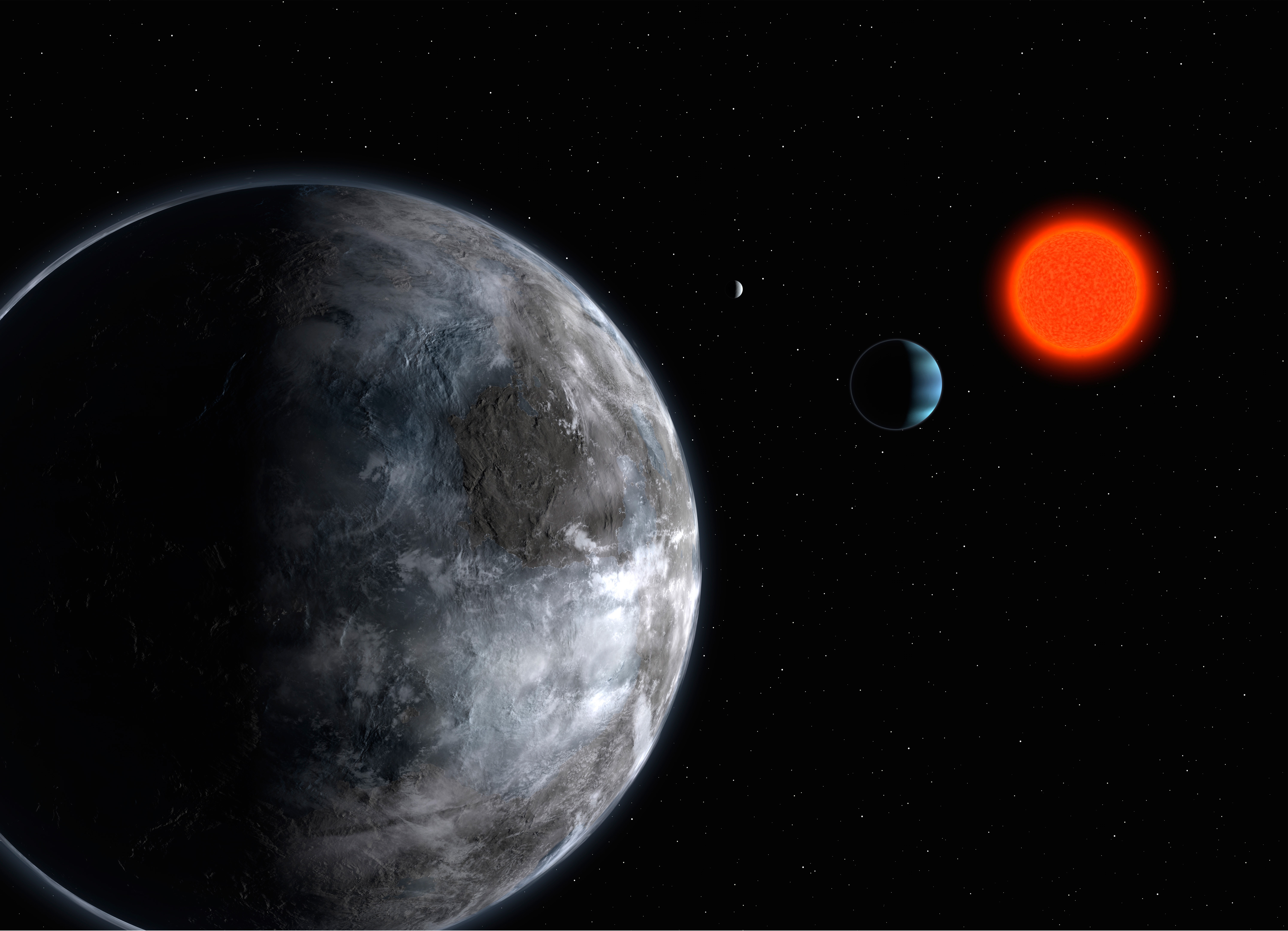

assume that the laws of Science apply on Gliese 581g just as precisely as those

laws apply here on Earth, as they also will here on Earth 100,000 years from

now. (Dennis Overbye sums up the debate in a 2007 New York Times article.1)

To some readers this assumption may seem so self-evident that stating it

is silly. But that reaction is too hasty. This basic assumption informs and

shapes all else that we contemplate and do. It deserves a bit more study and

analysis.

This basic belief in the universality of the laws of Science was not

always part of human thinking. We can clarify the modern way of seeing the universe by simply asking: “A consistent

universe? As opposed to what?”

Artist’s

conception of the Gliese 581 system

(credit: ESO/L. Calçada,

via Wikimedia Commons)

The alternative view of our universe sees it as being made up of regions

or eras in which different sets of rules apply or once did apply. This was the

view of our forebears. They saw a universe being run by many varied and

mutually hostile gods, each with his or her own realm and set of rules.

For example, for the ancient Greeks, Poseidon ruled the sea; he could

make storms at will and bring them down on any mariners he disliked. Hades

ruled the underworld, Zeus, the skies. Hades seized Persephone and took her to

his realm; even Zeus could only negotiate to get her back to her mother for

half the year. From this quarrel came the seasons. When Pers is with her mom,

the weather is mild. When Pers goes back to Hades, the winter comes. Two brats

who could not get along, and who happened to be supernatural, cause the seasons.

The ancient Greeks believed they lived in a universe run by lust, rage,

obstinacy, and cruelty. But today, we know exactly why the seasons occur. We

find the old belief amusing, quaint perhaps. But no one takes it seriously.

“The

Return Of Persephone”

(credit:

Frederic Leighton, via Wikimedia Commons)

The classical Greeks also accepted that their ancestors had been much

stronger than they were. Repeatedly in The Iliad, heroes hoist

rocks that “no man today could lift,” and they do it with ease.2 In

such a universe, ideas that were right in one era might be quite different from

those that were right (in both senses of right: physically accurate and moral) in a later or

earlier era.

But in the modern view, under Science, we assume all events have

rational explanations, and that the laws describing the strong force, the weak

force, electromagnetism, and gravity apply everywhere and always have done so.

It is true that we have not yet found a way to translate our model of gravity

into the system of ideas that describes the other three, but we are confident

that a unified field theory does exist. Ours is a single coherent universe, we

assume.

Do most people in our modern society truly believe the universe is a

single, coherent system? Yes. That view is the view that Science begins from.

The alternative – superstition – is simply not palatable for most people in the

West today. Whatever the flaws in the current scientific worldview – and it is

not logically airtight, as we have seen – we’ve nevertheless seen it achieve

far too many successes to gamble on any of its superstitious alternatives.

People in the West today, by and large, do not take a sick child to a

shaman for treatment. They go to a Western doctor. Who today would try to fix a

car problem by burning incense sticks or chanting? Farmers everywhere look to

scientists for advice on which crops to grow and which fertilizers to use. The

evidence indicates that heeding Science is a smart gamble, a wise Bayesian

choice, therefore, a rational one.

Let’s keep this first implicit assumption of Science in mind: in this

universe, all is connected to all else in a coherent way. (Maxwell discusses

this view and its problems at length in his book From Knowledge to

Wisdom, pp. 107–109.) 3

Second, we also have evidence now for the belief that this universe is, in

a way, aware. Changes in one part of the universe can produce changes in other,

distant parts – instantly. The parts of the universe connect in amazing ways.⁴

How parts connect is still a mystery to physicists, but that they are connected

is no longer in doubt. This phenomenon is called entanglement. Research

has verified it many times.

Quantum research tells us actions and reactions sometimes connect the

tiniest particles so that action and reaction occur like one event. Reverse the

spin of one particle here, and its partner particle – untouched by anything – will

reverse its spin at that same instant even if it is on the other side of the

universe! And the information passes from the first particle to its partner

instantly. Not at the speed of light – which Einstein said was the speed limit

of the universe – but instantly by some so far inexplicable means that physicists call entanglement.

Physicists have proved that entanglement is real as surely as they have

shown that Relativity Theory works or that electricity is connected to

magnetism. (Josh Roebke describes this research in an article published in

2008.)5

If we are to build a moral code based on the facts of the physical

universe, our code must be consistent with the idea of entanglement. Thus, it

is rational for us to choose to see the universe as being not just coherent,

but conscious. The universe “feels”

itself all over, all at once, all of the time.

And let’s remind ourselves here that Quantum Theory works. It is what

many technologies in our modern world spring from. It even fits daily life the

way we live it. It pictures us as having a degree of free will. Belief in free

will is the belief that allows me to hold people responsible for their actions.

In reality, the majority of us don’t live daily life as if the cars

around us in traffic are driven by unchangeable forces toward inescapable

outcomes. Cars contain drivers who are responsible beings. If they aren’t, they

shouldn’t be driving. If your car drifts out of its lane, and I have to steer

sharply left and almost swerve into oncoming traffic, I’m going to be mad at

you, not your car. (Get off your cell!!) Similarly, I reject any moral code

that excuses felons as not being responsible for their actions. Quantum Theory

endorses a picture of reality that allows for free will. Thus, with its

sub-concept entanglement firmly attached, Quantum Theory corroborates the

“feel” of daily life.

Therefore, I propose that this model that we get from Physics justifies

our inserting a further basic concept into our total worldview and, thus, into

our moral system: the universe is a single, integrated, coherent thing that is also

a kind of conscious. We can rationally insert this second idea into our moral

thinking. This view of the universe fits the evidence. As opposed to what? The

alternative view of the universe as utterly unfeeling and insentient, the view

of Newton and Laplace, does not fit the evidence we get from quantum research.

Now, let’s see where this subtler view of physical reality leads.

If we see our universe as being both coherent and conscious,

is this view nuanced view enough to justify theism? No. We need one more

idea.

The third big background idea in the case for my thesis is the one this

book has labored long to prove. It is the belief that there is a moral order in

this universe, a moral order that is observably, empirically real.

The universe runs by laws that cause patterns in the flows of physical

events. Our moral values guide us onto the best survival paths as we move

through these events. Our values are not visible. But we can see that they were

learned by our forbears, by trial and error, over millennia and that people who

lived by these values survived. Therefore, our core values – love, freedom,

wisdom, and courage – are real. They are like electromagnetism and gravity in one

crucial sense: they names things that we can’t see except by the effects they

have on things that we can see.

Again, we can ask about this third big idea: “As opposed to what?”

The idea usually opposed to moral realism in our times is moral

relativism. In its view, values are only tastes, and right and wrong depend on

where you are. The moral relativists say that what was right in Rome in the

first century is not morally right today; what is right in East Africa is not

right in Western Europe. For the moral relativists, there are no physical facts

that can tell us anything about what right is. For them, no values are ever

grounded in reality.

In this view, I have shown, they are wrong. Values are based in material reality.

Now, add all these three big ideas together.

The universe is a single, integrated thing.

The universe is also conscious.

The universe is also moral.

None of these claims is supported by perfect, irrefutable logic. All of

them are supported by solid Bayesian estimates of their likelihood. Each one of

them is a much more rational choice than its alternatives.

If, as a modern human in touch with the basics of Science in all its

forms, I believe the universe is a single, integrated thing – even if we do not

understand all of its laws – and I further believe it is a kind of conscious –

even if its consciousness is so vast and subtle that humans have barely begun

to grasp it – and I further believe it is morally responsive – even if its

moral quality is only discernible in the flows of millions of people over

thousands of years – if I believe these three claims, then in my personal way, I do believe in God.

What? That’s it?

Yes, my patient reader. That’s it. I do still believe in God. My view is

a pretty lean one. No sacred texts, holy men, miracles, or rituals. But every

instinct in me tells me that it is a wise, sane, Bayesian gamble at the base of

my thinking, where I must gamble on some sort of worldview if I am to function.

I can’t be neutral about the base of my own sanity. Theism is the most

rational of all the possible bases for the worldview I use to run my life and maintain

my sanity.

And as far as the leanness of this kind of theism goes, I say: “Such is

life.” Adults have to get by on leaner fare than do children who seek a bearded

man in the sky. For adult citizens in a democracy, life is labor and hazard

much of the time. But the best consolation of adult life is the firm belief

that the patterns we see in the flows of human events in the world – patterns

that only show in the evidence of centuries of human actions – are real.

Your deep intuition that courage, wisdom, freedom, and love are real, and most

of all, that right is real, is not naïve or crazy. It is the sanest

belief you have.

How can an informed human being in

modern times find balance between Morality and Science? By building their own

version of theism. Belief in God.

Now, in a personal expanding of this case for theism, let me show that it

is strong enough to support a more profound, comprehensive belief in God. And personal is

the word to use to describe my next chapter. In the end, theism has to be

personal or it is nothing at all.

Notes

1. Dennis Overbye, “Laws of Nature, Source Unknown,” New York

Times, December 18, 2007.

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/18/science/18law.html? pagewanted=all&_r=0.

2. Homer, The Illiad (c.

800–725 BC; Project Gutenberg), p. 91.

3. Nicholas Maxwell, From Knowledge to Wisdom: A Revolution for

Science and the Humanities (London, UK: Pentire Press, 1984), pp.

107–109.

4. http://www.wired.com/2013/12/secret-language-of-plants/

5. Joshua Roebke, “The Reality Tests,” Seed magazine,

June 4, 2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.