Chapter 20 The

Theistic Bottom Line

The three large principles summed up in

the previous chapter are enough. The universe is coherent, conscious, and moral.

Having established these principles, we have enough to conclude that a consciousness

exists in our material universe. Or rather, as was promised in the

introduction, we have enough to conclude that belief in God is a rational

choice for an informed modern human being to make, a rational gamble to take.

More rational than any of its alternatives.

And that’s the point. Belief in God is

a choice. It is simply a more rational choice than its alternatives, and it

arises naturally once we understand the key ideas of the main branches of

Science – entropy, uncertainty, and evolution – and then further see that our

moral values are based on these ways of the real world.

Our values are grounded in empirical

reality. And seeing that values are real is the key step that enables us to

cross from doubt to theism.

But now in this chapter I will examine many pieces of supporting argument and evidence that give this case for theism a sense of both universality - it fits the facts of physical reality - and immediacy - it speaks to each of us in ways that feel personal. Heartfelt, as a belief must be if it is to endure. Its carriers must care about it if it is to be transmitted to the next generation.

At this stage of our discussion, it is

also worth reiterating two other points made earlier: first, we must have a

moral program in our heads to function at all; second, the one we’ve inherited

from the past is dangerously out-of-date.

But all of this chapter so far has just summed up the case we have already made.

I can now give a more informal

explanation of the argument we have assembled, then even more arguments whose

special significance in this discussion will be explained as we go along. We

will make the case personal and also try to answer some of the most likely

reactions to it.

Let's get more deeply into this last

chapter by revisiting a vexing problem in Philosophy mentioned in Chapter 4, a

problem that is nearly three hundred years old. The solution to this problem

drives home a main point on the final stretch of the thinking that leads to

theism. Even though it is a gamble to believe the universe is a single

conscious system, it is a rational gamble.

Many scientists claim that Science,

unlike the other branches of knowledge that came before the rise of Science,

does not have any assumptions at its foundation and that it is instead built

from the ground up on merely observing reality, forming theories, designing

research, doing experiments, checking the results against one’s theories, and

then doing more hypothesizing, research, and so on. Under this view, Science

has no need of foundational assumptions in the way that, say, Plato’s philosophy

or Euclid’s geometry do. Science is founded only on hard, observable facts,

they claim.

But in this claim, as has been pointed

out by thinkers like Nicholas Maxwell, the scientists are wrong.1 Science

rests on some assumptions that are so basic that they can seem obvious. Beyond

dispute. But they are still assumptions.

The book that told the world how Science should work: Novum Organum

(credit: John P. McCaskey, via Wikimedia Commons)

The heart of the matter, then, is the

inductive method normally associated with Science. The way in which scientists

can come upon a phenomenon they cannot explain by any of their current

theories, devise a new theory that tries to explain the phenomenon, test the

theory by doing experiments in the real world, and keep going back and forth

from theory to experiment, adjusting and refining – this is the way of gaining

knowledge called the scientific method. It has led us to many

powerful insights and technologies.

But as Hume famously proved, the logic

this method is built on is not perfect. Any natural law we try to state as a

way of describing our observations of reality is a gamble, one that may seem to

summarize and bring order to whole files of experiences, but a gamble,

nonetheless.

A natural law statement is a scientist’s

claim about what he thinks is going to happen in specific future circumstances.

But every natural law proposed is taking for granted a deep first assumption

about the real world. Every natural law statement rests on the assumption that

events in the future will continue to steadily follow the patterns we have been

able to spot in the events in the past. But we simply can’t know whether this

assumption is true. We haven’t been to the future. Thus, we must allow for the

possibility that at any time, we may come on new data that stymie our best

theories. Thus, we must accept that every natural law statement, no matter how

well it seems to fit real data, is a gamble. It gambles on the belief that the

future will go like the past.

Science is made up of a large group of

terms, concepts, claims, and records that are all gambles. Some very likely to

be true, some very speculative, the rest somewhere in between these two

extremes.

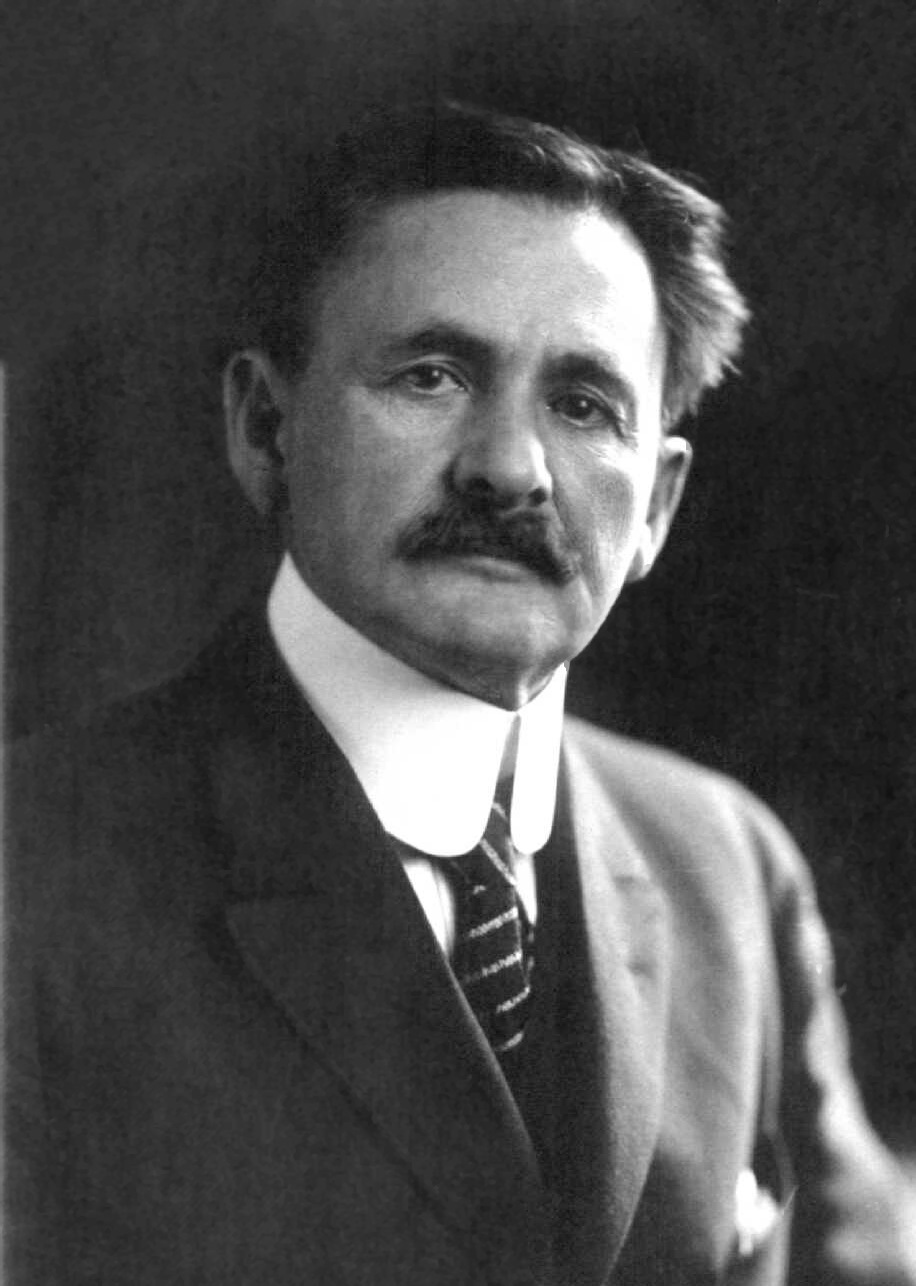

Albert Michelson

(credit: Bunzil, via Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Morley (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Science makes mistakes. For scientists

themselves, a shocking example of such a mistake was one in Physics. Newton’s

model of gravity and acceleration was brilliant, but it wasn’t telling the full

story of what goes on in our universe. After two centuries of taking Newton’s

equations as their gospel, physicists were stunned by Michelson and Morley’s

experiment in 1887. In essence, it showed that Newton’s laws weren’t adequate

to explain all that was going on, especially at very high speeds or with very

large masses.

Einstein’s pondering these new data is

what led him to the Theory of Relativity. But first came Michelson and Morley’s

experiment, which showed Newton’s shortcomings, and also showed that the

scientific method was not infallible.

Newton was not proved totally wrong,

but his laws were shown to be only approximations, accurate only for smaller

masses at slow speeds. As masses or speeds become very large, Newton’s laws

become less useful for predicting what is going to happen next.

Nevertheless, it was a scientist,

Einstein, doing science who found the limitations of the theories and models

specified by an earlier scientist. Newton was not amended by a clergyman or a

reading from an ancient holy text.

Thus, from the personal standpoint, I

have always believed, I still believe, and I’m confident I always will believe

that the universe is consistent, that it runs by laws that will be the same in

2525 as they are now, even though we don’t understand all of them yet. Yes, the

future – not in every detail, but in the big ways – will go like the past. Entropy.

Uncertainty. My choice to gamble on Science is a good Bayesian gamble,

preferable to all superstitious alternatives.

As a believer in Science, I also choose

to gamble on the power of human minds, sometimes alone, sometimes in

cooperation with other minds, to see through the layers of irrelevant, trivial

events and spot the patterns that underlie large sets of data. We can figure

this place out and gradually get more and more power to move about in it

without getting hurt or killed.

The alternative to believing in the

power of human minds – individually or in cooperating groups – to figure out

the laws which underlie reality is to abandon reason and gamble instead on

beliefs that are not based on observations of facts. Once again, we have the

evidence of centuries of history to look back on. All the evidence we have

about what life was like for the cowed, superstitious tribes of the past

suggests that their lives were – as Hobbes put it – poor, nasty, brutish, and

short. People who were willing to think about the real world they could

observe, experiment with it, and learn from it, made the society we enjoy

today. Even the most obstinate of Luddite cynics who claim to despise modernity

don’t like to go two days without a shower.

My first point in this final chapter on

the path to a personal kind of theism, then, is that belief in the consistency

of Science – i.e. of the laws of the universe and the power of human minds to

figure them out – amounts to a kind of faith. Yes, faith. Belief in ideas that

are so basic that they cannot be proved by some other more basic ideas. For

Science, there are no ideas more basic than the ones that say the universe is a

single, coherent system and that we humans can figure out how that system

works. The rest of Science rests on those assumptions.

Atheists say these beliefs can’t be

called “faith” at all. They certainly don't lead to a belief in God. They just

enable atheists and theists alike to do Science. To share ideas, theories,

models, and research in their branches of Science with anyone who’s interested.

But these are beliefs in the long-term validity of concepts that can’t be demonstrated.

And that is a kind of faith.

Now let’s add some other powerful ideas

to this personal case for theism. If we truly believe in Science, then we

are committed to integrating into our thinking all well-supported theories in all

the branches of Science. In this century, that means we must try to integrate

Quantum Theory into our world view.

Earlier we saw that extrapolating from the quantum model led us to see that the values we call freedom and love are real. The quantum picture of the universe gives us solid grounds for belief in our own free will. And widespread belief in free will creates a society which survives. People who live by these values practice behaviors that suit the probabilistic nature of reality and, thus, they improve their society’s survival odds. Live by both freedom and love. Then as a consequence, it is more likely that you’ll survive and your descendants will and so on.

The best of our ancestors lived by the

values implicit in the quantum worldview, the free will view, centuries before

there was any scientific research to show us that the universe is founded on

probabilities, not the irrevocable chains of cause and effect that the Newtonian worldview forces on us. But we today have a worldview supported by research – the quantum worldview – to fit together with the

moral code that tells us to practice freedom and love.

From Physics, we get quantum

uncertainty, and from Moral Philosophy, freedom and love. Quantum Theory

supports Moral Philosophy and vice versa; the concepts fit together; they fit

human minds and cultures into reality as Science describes it for us. Taken together,

they make a sensible gamble.

Erwin Schrodinger (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

However, the quantum worldview, if we

choose to follow it, comes with some startling implications. Quantum entanglement,

and the experiments testing it, have shown us that particles all over the

universe are in instant communication with each other all the time. This model

implies that the universe is conscious.

The universe is not, as pre-quantum science pictured it, totally Newtonian and local. It is capable of what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance,”. In fact, it works that way all the time.5 Schrodinger said: “There seems to be no way of stopping [entanglement] until the whole universe is part of a stupendous entanglement state.”6

Why does the quantum view matter so

much to our case for theism? Because if we think distant parts of an entity are

in touch with one another (in the case of the universe, instantly), it is

entirely reasonable to further postulate that there must be an entity, a conscious thing of

some kind, connecting the stimulus of one particle to the response by another particle in a distant location.

The universe is a single, coherent entity that feels.

This way of seeing the universe as being

a kind of aware is my second big idea in this final, personal chapter of my

argument. It is well known to scientists, theist and atheist alike. They admit

that understanding entanglement does move us a bit closer to believing that

some sort of a God may exist.

Murray Gell-Mann, Nobel Prize–winning physicist

(credit: Wikipedia)

But according to science-minded

atheists, these ideas – about how the

universe is a single consistent entity and how it seems to have a kind of

awareness – even taken together, only add up to a trivial belief. A proposal we

can consider, but then drop because there is too little evidence to support it

and, in addition, it leads nowhere. It does not enable human minds to imagine

any new models of reality, nor to devise any new way of testing such models. Physicist

Murray Gell-Mann went so far as to derisively call this way of thinking

“quantum flapdoodle.”7

In other words, we may have deep

feelings of wonder when we see how vast and intricate the universe is – far

more amazing, by the way, than any religion of past societies made it seem. Our

intuition may even suggest that for information to travel instantly from one

particle in one part of the universe to another particle in another vastly

separated part, a consciousness of some kind must be joining the two. But these

feelings, the atheists say, don’t change anything. According to science-minded

atheists, the God that theists describe doesn’t answer prayer, doesn’t grant us

another existence after we die, doesn’t perform miracles, and doesn’t care a

hoot about us or how we behave.

Pierre-Simon de

Laplace (via James Posselwhite, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the atheist view, believing in such

a God is simply excess baggage. It is a belief that we might enjoy clinging to

as children, but it is extra, unjustified weight that only encumbers the active

thinking and living we need to practice if we wish to keep expanding our

knowledge and living in society as responsible adults. Theism, the atheists

say, hobbles both Science and common sense. Or as Laplace famously told

Napoleon, “Monsieur, I have no need of that hypothesis.”

William of Occam,

English philosopher and theologian

(credit: Andrea di Bonaiuto, via Wikimedia Commons)

Centuries ago, William of Occam said

the best explanation for any phenomenon is the simplest one that will do the

job. Newton reiterated the point: “We are to admit no more causes of natural

things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.”8 If

we can explain a phenomenon by using two basic concepts instead of three or

four, we should choose the two-pronged tool.

According to atheists, belief in God –

or at least in a God that might or might not exist in this coherent, entangled,

apparently self-aware universe – is a piece of unneeded, dead weight. In our

time, under the worldview of modern Science, the idea has no useful content. It

can and should be dropped. Or as the sternest atheists put it, it is time that

humanity grew up.

Starry

Night at La Silla Observatory, Chile

(credit: ESO/H. Dahle, via Wikimedia Commons)

The model of cultural evolution

developed in this book undoes the cynicism of such atheists. Under moral

realism, values are real, we are going somewhere, and whether we behave morally

or immorally does matter, not just to us in our limited frames of reference,

but to the consciousness that underlies the universe. That presence, over

millennia, helps the good to thrive by maintaining a reality in which there are

lots of free choices and chances to learn, but also a long-term advantage to

those who strive to perform actions that balance courage, wisdom, freedom, and

brotherly love.

This is the third big idea in my

overall case for theism: moral realism. First, we see the universe as a

consistent, coherent system; second, we see it as conscious; third, we see our

values as being connected to the universe in a physical way.

Why does this third insight matter so

much? Because it refutes everything else atheists claim to know. Under the

moral realist model, our values are the beliefs that maximize the probability

of our survival. The moral realist model guides us to formulate and live by

values that work. Trying to be good matters.

Thus, moral realism is not trivial. It

is vital. How you act is going to contribute in real ways to the survival odds

of you, your children, and your species. The way to act if you want to improve

the odds of all of those things surviving begins by your living under the

large values of courage, wisdom, freedom, and love. Therefore, decency and

sense are embedded in the particles of reality itself.

The inescapable implication of seeing moral values as being arbitrary and trivial is seeing one's own existence as trivial. And for real people living real lives, that just is not how life works, makes sense or, more basically, feels.

Belief in the realness of values is

not trivial just as belief in the consistency of the universe is

not trivial. Both beliefs have an effect – via the kinds of thinking and

behavior they cause in us – on the odds of our survival. In the long haul,

Science is good for us. So is Moral Realism. People who carry these programs in

their heads outwork, outfight, outbreed, and outlast the competition. Moral

Realism's worldview does describe reality. Our reality.

Thus, belief in the realness of our

values enables us to see that the presence that fills the universe doesn’t just

stay consistent and even have a kind of awareness. It also favors those living things

that follow the ways we call “good.”

It cares.

In my own intellectual, moral, and

spiritual journey, I went a long time before I could admit even to myself that

by this point I was gradually coming to believe in a kind of deity. God.

Fourteen billion light years across the

known parts of the universe. Googuls of particles. 1079 instances

of electrons alone, never mind quarks or strings. And all integrated parts of

one thing -- consistent, aware, and compassionate, all over,

all at once, all the time.

And these claims describe only the

files of evidence we know of. What might exist before or after, in smaller or

larger forms, or even other dimensions and alternate universes that some

physicists have postulated? We can’t even guess.

And it cares.

Every idea about matter or space that I

can describe with numbers is a naïve children’s story compared with what is

meant by the word infinite. Every idea I can talk about in terms

that name bits of what we call “time” must be set aside when I use

the word eternal. For many of us in the West, formulas and graphs,

for far too long, have obscured the big ideas, even though most scientists

freely admit there is so much that they don’t know.

Isaac Newton said: “I seem to have been

only a boy playing on the seashore, diverting myself in now and then finding a

smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of

truth lay all undiscovered before me.”9

And it cares.

With beliefs in the coherence shown by

Science, in the Universal Awareness we see in Quantum Theory, and in Moral

Realism firmly in place, Wonder arrives.

This way of living resolutely by moral

guidelines whose consequences may take generations to arrive is exactly what is

meant by the word faith. Belief in things not seen.

This theistic view,

when it’s widely accepted in society, also is utterly consistent with Science.

A general adherence in society to the moral realist way of thinking is what

makes communities of scientists doing Science possible.

Consciously and individually, every scientist should value wisdom and freedom, for reasons that are uplifting, but even more because they are rational. Or rather -- to be more exact -- rational and uplifting, fully understood, turn out to be the same thing. As Keats told us, beauty is truth, truth beauty.

Scientists know that figuring out how

the events in reality work is personally gratifying. But more importantly, each

scientist should see that this work is done most effectively in a free, interacting

community of scientists functioning as one sub-culture in a larger social

ecosystem where freedom and love reign.

Many of us in the West have become

deeply attached to our belief in Science. We’ve been programmed to feel that

attachment. We believe our modern wise men – scientists – doing and sharing research

are vital to our survival. And of all the subcultures within

democracy that we might point to, none is more dependent on moral realist values

than is Science.

Scientists have to have courage.

Courage to think in unorthodox ways, to outlast neglect, even ridicule, and to

work, sometimes for decades, with levels of dedication that people in most

walks of life find hard to believe. (Yes, decades. Many, even after decades of

research on the particular problem they have chosen to study, die with that

problem unsolved.)

Scientists need a profound form of

wisdom. Wisdom that counsels them to listen to analysis and criticism from

their peers without allowing egos to cloud their judgement, and to sift through

what is said for insights that may be used to refine their theories and methods

and try again.

Scientists need freedom. Freedom to

pursue Truth where she leads, no matter whether the truths discovered are

unpopular or threatening to the status quo.

Finally, scientists must practice love.

Yes, love. Love that causes them to treat every other human being as an

individual whose unique experience and thought may prove valuable to their own.

Science is only viable in such a community.

Scientists recognize that no one human

mind can hold more than a tiny fraction of all there is to know. They must

respectfully share and peer-review ideas and research in order to advance, individually

and collectively.

Scientists do their best work in a

community of thinkers who value, respect and love one another, so

automatically, that they cease to notice another person’s race, religion,

sexual orientation, etc.. Under the cultural evolution model, one can even

argue that democracy’s largest purpose has always been to create a social

environment in which Science can flourish.

But these are just pleasant

digressions. The main implication of the moral realist way of thinking is even

more personal and profound, so let’s return to it.

The universe is coherent, aware, and compassionate.

Belief in each of these qualities of reality is a separate, free choice in each

case. Modern atheists insist that far more evidence and weight of argument exist

for the first than for the second or third of these three beliefs. My

contention is that this is no longer so. Once we see how our values connect to

reality, the theistic choice becomes a reasonable one and an existential one.

It defines who we are.

Therefore, belief in God emerges out of

an epistemological choice, the same kind of choice we make when we choose to

believe that the laws of the universe are consistent. Choosing to believe,

first, in the laws of Science, second, in the self-aware universe implied by

quantum theory, and third, in the realness of the moral values that enable

democratic living (and Science) entails a further belief in a steadfast, aware,

and compassionate universal consciousness. God.

Belief in God follows logically from my

choosing a specific way of viewing this universe and my integral role in it:

the scientific way.

The biggest problem for stubborn

atheists who refuse to make this choice is that they, like every other human

being, have to choose to believe in something.

Each of us must have a set of

foundational beliefs in place in order to function effectively enough to move

through the day and stay sane. The Bayesian model rules all that I claim to

know. I have to gamble on some set of axioms in order to move through life. The

only real question is: “What shall I gamble on?”

Reason points to the theistic gamble as

being not the only choice, but the wisest choice of the epistemological choices

before us. I’m going to gamble that God is real. As far as I can see, I have to

gamble on some worldview, and theism is the best gamble. It makes all my ideas

come together into one coherent system that I can follow readily as I make

choices and implement them in all aspects of life.

Theism - belief in a single, conscious, compassionate entity that is present in all the universe all the time - is simply more efficient than any competing way of thinking ever could be. Theism makes effective, timely action possible.

Theism - belief in a single, conscious, compassionate entity that is present in all the universe all the time - is simply more efficient than any competing way of thinking ever could be. Theism makes effective, timely action possible.

The best gamble in this gambling life

is theism. Reaching that conclusion comes from looking at the evidence.

Following this realization up with the building of a personal relationship with

God, one that makes sense to you as it also makes you a good friend – that,

dear reader, is up to you. Do it in a way that is personal. That is the only

way in which it can be done truly, if it is to be done at all.

To close in an unashamedly personal way, then.

Once one truly believes in the theistic conclusion, does life remain hard? Of course. Adversity is an inherent feature of life in this universe. But we evolved to work. If life got easy, we would long for challenge. And please note that life has been safe for some spoiled children of the rich. For a while. But those who don't know challenge, know ennui. Meaninglessness. Look at the evidence.

Will life remain scary, uncertain, if one sees that theism really does make sense? Of course. But seeing the whole picture also affirms for us that the upside of living in a stochastic universe is freedom. Uncertainty/anxiety is the price of freedom. The joy and the fear of conscious existence. The best response to such a realization is more than just work. It is imagination. Creativity. Best of all, we realize that permeating this whole way of thinking is the knowledge that love is real. Love will triumph if we practice it well. That's how reality is built.

Notes

1. Nicholas Maxwell, Is Science

Neurotic? (London, UK: Imperial College Press, 2004).

2. “History of Science in Early

Cultures,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia.

Accessed May 2, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_in_early_cultures.

3. Mary Magoulick, “What Is

Myth?” Folklore Connections, Georgia College & State

University.

4. “Pawnee Mythology,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May 2, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pawnee_mythology.

5. “Quantum Entanglement,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May 2, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_entanglement.

6. Jonathan Allday, Quantum

Reality: Theory and Philosophy (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2009), p.

376.

7. “Quantum

Flapdoodle,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Accessed May 2,

2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_mysticism#.22Quantum_flapdoodle.22.

8. “Occam’s Razor,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May 4, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor.

9. “Isaac Newton,” Wikiquote, the Free

Quote Compendium. Accessed May 4, 2015.http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.