Chapter 6 Rationalism

and its Flaws

In Western philosophy, the main alternative to Empiricism for

describing the mind and, thus, giving us a model of knowing, is called

“Rationalism”. It is the way of Plato in Classical Greek times and of Descartes

in the Enlightenment.

Rationalism claims that the mind can build a system for understanding

itself, and for how it “knows” about its world, only if that system is first

grounded in the mind by itself, before any sensory experiences or

memories of them enter the system. Rationalism says you can know truth by

beginning inside the confines of your own mind. In fact, that is the only

reliable way to know truth.

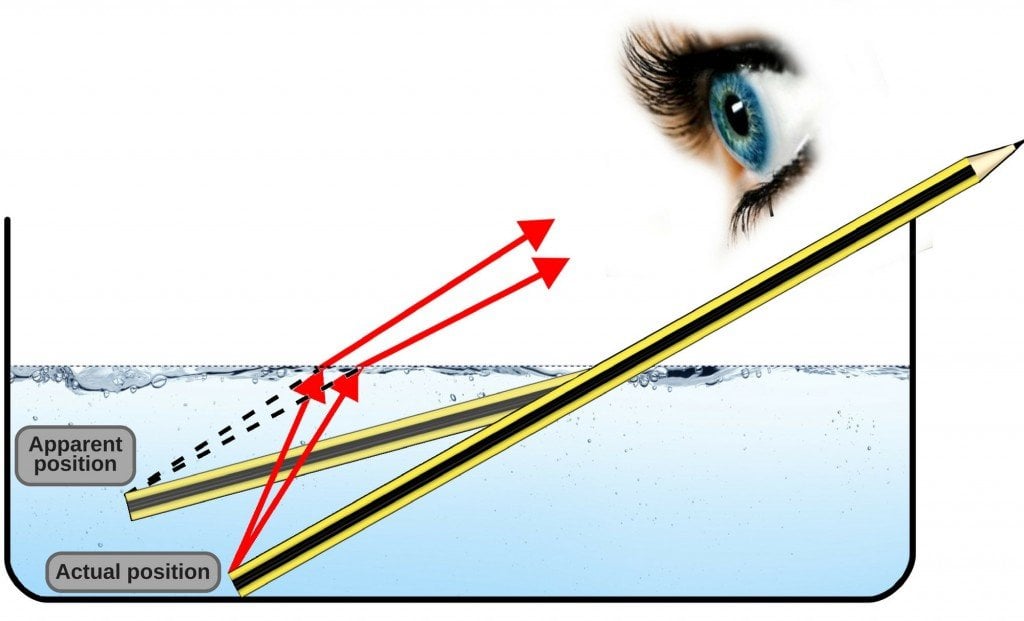

(credit: scienceabc.com)

Descartes, for example, points out that our senses give us information

that can easily be faulty. As was noted above, the stick in the pond looks bent

at the water line, but if we remove it, we see it is straight. The hand on the

pocket warmer and the hand in the snow can both be immersed shortly after in

tepid tap water; to one hand, the tap water is cold and to the other, it is

warm. And these are the simple examples. Life contains many much more difficult

ones.

Therefore, the rationalists say, if we want to understand thinking in a reliable

way, we must construct a model of thinking that is based only on concepts that

are built into the mind itself, before any unreliable sense data or memories of

sense data even enter the picture.

Plato says we are born already dimly knowing some perfect forms that

we then use to organize our thoughts. He drew the conclusion that these forms,

which enable us to make sense of our world, are imperfect copies of the perfect

forms that exist in a perfect dimension of pure thought, before birth, beyond

matter, space, and time – a dimension of pure ideas. The material world and the

things in it are only poor copies of pure forms ultimately derived from the

pure Good. The whole point of our existence, for Plato, is to discipline the

mind by study until we learn to recall, understand, and navigate through life by,

the perfect forms – perfect tools, perfect medicine, perfect beauty, perfect

houses, perfect animals, perfect justice, perfect love, and so on.

Descartes’ similar system of thought begins from the truths the mind

finds inside itself when it carefully, quietly contemplates only itself. During

this totally concentrated self-contemplation, the thing that is most deeply

you, namely your mind, realizes that whatever else you may be mistaken about,

you can’t be mistaken about the fact that you exist; you must exist

in some way in some dimension in order for you to be thinking about whether you

exist. For Descartes, this was a rock solid starting point that enabled him to

build a whole system of thinking and knowing that sets up two realms: a realm

of things the mind deals with through the physical body attached to it, and

another realm the mind deals with by pure thinking, a realm built on the clear

and distinct ideas (“clarus et

distinctus essentiam”) that the mind knows before it takes in any

impressions coming from the physical senses.

In our last chapter, the moral philosophers’ hope of finding a

foundation for a moral system in Empiricism was dashed by Gödel and other

thinkers like him. Rationalism’s flaws have been just as clearly exposed by

psychologists such as Elliot Aronson and Leon Festinger.

Elliot Aronson (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Aronson was Festinger’s student. He went on to win much acclaim in his

own right. They both focused their work on cognitive dissonance theory, which

describes a human mental habit. The theory is fairly easy to understand, but

its consequences are profound and far-reaching. The theory says that the

inclination of our minds is always toward finding reasons and evidence to

justify what we want to do anyway, and even more firmly believed ones to

justify the things we’ve already done. (See Aronson’s The Social Animal.1)

What it says essentially is this: the mind tends, insistently and

insidiously, to think in ways that affirm itself. In every action the mind

directs the body to perform, and in every phrase it directs the body to utter,

it tends to try to stay consistent with itself. In practice, this means humans

tend to find reasons for maintaining the way of life in which they’ve become

comfortable. Reasons that sound “good”

to them. Every mind strives to make theory match practice or practice match

theory – or to adjust both – in order to reduce internal feelings of

discomfort. (“Am I being a hypocrite here?” we ask ourselves.) This mental

discomfort is what psychologists call cognitive dissonance.

A novice financial advisor who used to speak disparagingly of all sales

jobs is now able to tell you with heartfelt sincerity why every person,

including you, ought to have a thoughtfully selected portfolio of stocks.

A physician adds another set of therapies, of dubious effectiveness, to

his practice every year. A plastic surgeon can show with argument and evidence

that the cosmetic procedures he performs should be covered by the state’s

health-care plan because his patients are “aesthetically handicapped.”

The divorce lawyers are not setting two people who used to love each

other at each other’s throats. Each is merely defending his or her clients’

interests, while the clients’ misery grows worse every week the case goes on.

The cigarette company executive not only finds what he believes are

flaws in the cancer research, he smokes over two packs a day.

The general sends his own son to the front. And his mother-in-law’s

decent qualities, not her rude ones, become more obvious to him on the day he

learns that she owns over ten million dollars’ worth of real estate. (All that

landlord-stress! No wonder she’s sometimes rude.)

What of the Philosophy professor, who is trained to spot bad logic? He

once said he believed in the primacy of the rights of the individual over any

group’s rights. He sought to abolish any taxes that might be used to pay for

social services. Private charities could do such work if it needed to be done

at all. But then his daughter – who suffers from bipolar disorder and who

sometimes goes off her medications and runs away from all forms of care, no

matter how loving – runs off and becomes one of the mentally ill homeless in

the streets of a distant city. She is saved by alert street workers, paid

(meagrely) by the state. Now he argues that citizens should pay taxes that can

be used to hire street workers who look out for the vulnerable and destitute.

In addition, he once considered euthanasia to be totally immoral. But

now his aging father who has Alzheimer’s disease has been deteriorating for

over five years. Professor X is broke, sick, and exhausted. He longs for the

heartache to be over. He knows he cannot keep caring, day in and day out, for

the needs of this now unrecognizable, pathetic creature for very much longer.

Even Dad, the dad he once knew, would have agreed. Dad needs and deserves a

gentle euthanasia. Professor X is sure of it, and in confidential conversations,

he says so to his grad students and colleagues .

The two famous rationalists have had millions of followers, in

Descartes’s case for 400 years and in Plato’s case for well over 2000. These

Rationalists have attacked Empiricism for as long as it has been around. Since

the 1600s with Locke’s Empiricism, or even, arguably, since before 300 B.C., with

Aristotle’s version of Empiricism, which Plato and some of his followers

disputed.

Since Aristotle’s time, the debate between Rationalists and Empiricists

has not let up. But in our attempt to build a universal moral code, we find we must

discard Rationalism just as resolutely as we did Empiricism; Rationalism

contains a flaw worse than any of Empiricism’s flaws.

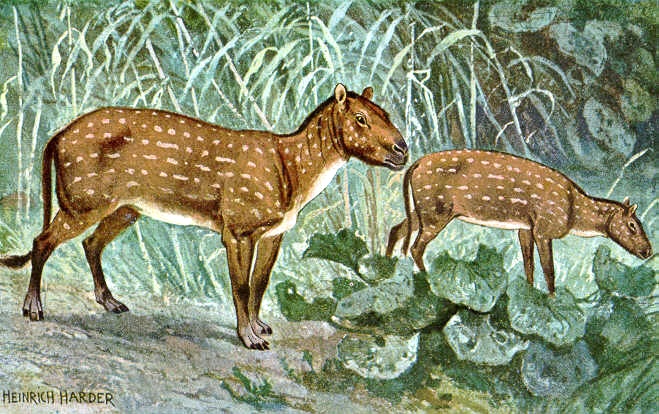

Eohippus (artist's conception)

(By Heinrich Harder [Public domain], via

Wikimedia Commons)

Do we, in our endlessly subtle rationalizations, see what is not there? Not really. A fairer way of describing the dissonance-reducing tendency in human minds is to say that, out of the billions of sense details, the googols of patterns we might see among them, and the infinite number of interpretations we might give to those details, we tend to choose those that are consistent with the view of ourselves that we find most comforting. We don’t like seeing ourselves as hypocrites. We don’t like feelings of cognitive dissonance. Therefore, we tend to be drawn to ways of thinking, speaking, and acting which reduce that dissonance. In short, deep down, we need to like ourselves.

There is nothing really profound being stated so far. But when we come

to applying this theory to philosophies, the implications are a little

startling.

Other than rationalizations, the Rationalists have nothing to offer.

What are Plato’s forms? Can I measure one? Weigh it? If I

claim to know the forms and you do too, how might we determine whether the

forms you know are the same ones I know? If, in a perfect dimension somewhere,

there is a form of a perfect horse, then what were eohippus and

mesohippus (biological ancestors

of the horse), who were horsing

around long before anything

Plato would have recognized as a “horse”

existed? Are eohippus fossils a lie?

Questions similar to the ones we can ask about Plato's rationalism, can be asked about Descartes' version. What are Descartes' clear and distinct ideas? Clear and distinct to whom? Him? His contemporaries? To me, they do not seem so clear and distinct that I can stake my thinking – and thus my sanity and survival – on them. Many people don’t know, and have never known, what he’s talking about. Not in any language. Yet they’re fully human folk. Descartes’ favourite clear and distinct ideas – the basic ideas of arithmetic and geometry – are unknown in some human cultures.

This evidence suggests strongly that Descartes’ categories are simply

not that clear and distinct. If they were inherent in all human minds, all

humans would contain these ideas from birth – which they clearly don’t. (A

point first noted by Locke.) Looking at a broad spectrum of humans, especially

those in other cultures, tells us that Descartes’s clear and distinct ideas are

not built in. We acquire them by learning them from other humans. Arguing that

they are somehow real, and that sensory experience is illusory, is a way of thinking

that can then be extended to arguing for the realness of the creations of the fantasy

writers. In The Hobbit, Tolkien describes Ents and Orcs. I go along

with the fantasy for as long as it amuses me. But there are no Ents, however

much I may enjoy imagining them.

In short, by a little reasoning, we can see that Rationalism undermines

itself.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1916) (credit: Wikipedia)

So, then, what are our concepts?

They are mental models that we devise to help us to organize our

memories. Our memories are what we consult as we go through the world and try

to act effectively. We invent concepts by looking over our

memories to find patterns. When we see a pattern, we put a concept-label on

that file of memories. The concept label helps us to sort through memories more

reliably and quickly so that in future we can make sound plans and act on them

in timely ways. If a concept regularly helps us to get good results, we keep

it. When it doesn't work well anymore, we look for a better tool. Almost,

but not quite, always. (Why I say “not quite always” I will be explain in

upcoming chapters.)

Even ideas of numbers, Descartes’s favorite “clear and distinct” ideas,

are just mental tools that are more useful than ideas of Ents. Counting things

helps us to act strategically in the material world and thus to survive.

Imagining Ents gives us temporary amusement – not a bad thing, but not nearly

as useful as an understanding of numbers.

But numbers, like Ents, are mental constructs. In reality, there are

never two of anything. No two people are exactly alike, nor are two trees, two

rocks, two rivers, or two stars. So what are we really counting? We are

counting clumps of sense data that roughly match concepts built up from

memories, concepts that were built on much larger banks of data, and that have

been tested and proven to be far more useful for survival than the concept of

an Ent.

Even those concepts that seem to be built into us (e.g. basic language

concepts) became built-in because, over eons of evolution of our species, those

concepts gave a survival advantage to their carriers. Language enables

teamwork; teamwork helps a human tribe to get things done. Thus, language is a

physically explainable phenomenon. It belongs in the fold of Empiricism.

Geneticists can locate the genes that enable a developing embryo to

build a language centre in the future child’s brain. Later, an MRI scan can

find the place in your brain where your language program is located. If you

have a tumor or an injury there, a neurosurgeon may fix the “hardware” so that

a speech therapist can then help you to fix the program. In other words, the

surgery on a physical part of you can give you back your ability to speak. Even

the human capacity for language is an empirical phenomenon.2

Stone

Age

(credit:

V. Vasnetsov, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the meantime, eons ago, counting enabled more effective hunter

behavior. If a tribe leader saw sixteen of the things his tribe called deer go

into the bush, and if he counted only fifteen coming out, he could calculate

that if his friends caught up, circled around in time, and executed well, and

if they worked as a team and killed the deer, this week the children would not

starve. Both the ability to count things and the ability to articulate detailed

instructions to other members of one’s tribe boosted an early tribe’s survival

odds. Similarly, the medicine woman taught her skills to her daughter. That’s

why numbers and words were invented and used and are still being used. They

work.

The basic concepts of math and language got built up in us because those

who had them and used them survived in greater numbers than those who

didn't.

If the precursors of language seem to be genetically built into us (e.g.

human toddlers all over the world grasp that nouns are different from verbs)

while the precursors of math are not, this only shows that basic language

concepts proved far more valuable in the survival game than basic math ones.

(Really crucial concepts, like our wariness of heights or snakes, got written

into our genotype long before language arrived.) The innate nature of language

skills, along with the usefulness of language, indicates that basic language

concepts do not come to us by any inexplicable process out of an ideal

dimension. All these human traits have material – i.e. Empiricist –

explanations.

We do not have to believe – as the Rationalists argue – in another

dimension of pure thought, with herds of “forms” or “distinct ideas” roaming

its plains, in order to have confidence in our own ability to reason. By

nature, nurture, or subtle combinations of the two, we acquire those concepts

that enable their carriers to survive. Then, we teach them to our kids. Our

ability to reason can be explained in ways that don’t assume any of what

Rationalism assumes.

And now Rationalism’s disturbing implications start to occur to us.

Wouldn’t I love to believe that there is some hidden dimension in which the

forms exist, perfect and eternal? Of course, I would. Then I would know I was

“right.” Then I and a few simpatico acquaintances might agree among ourselves

that we were the only people truly capable of perceiving the finer things in

life or of recognizing which are the truly moral acts. Our training and natural

gifts would have sensitized us to be able to detect the beautiful and the good.

For us to persuade the ignorant masses – by whatever means necessary – would

only be rational. Considering their inability to figure things out for

themselves, it would be an act of mercy for us to get control of the nation and

run it.

This view is not just theoretically possible. It was the view of some of

the disciples of G.E. Moore almost a century ago and, even more blatantly, of

the followers of Herbert Spencer a generation before that. (Explanations of the

views of Moore and Spencer can be found in Wikipedia articles online.3,4)

Herbert Spencer (credit: J. P. Burgess, via Wikimedia

Commons)

I am being sarcastic about the sensitivity of Moore’s and Spencer’s

followers, of course. Both my studies and my experience of the world tell me

there are more than a few of these sensitive aristocrats roving around in

today’s world, in every land (the neocons of the West?). We underestimate them

at our peril. The worst among them don’t like democracy. They yearn to be in

charge, they have the educations and inherited privileges to secure positions

of authority, and they have the capacity for lifelong fixation on a single goal,

namely, keeping their power. Further, they have the ability to rationalize

their way into believing that harsh or deceitful actions are sometimes needed

to keep order among the “brutishly ignorant masses” – i.e. everyone else.

Out of our discussion of Rationalism, the conclusion to draw is that too

often it is a companion of totalitarianism. The reason does not become clear till

we understand cognitive dissonance. Understanding how cognitive dissonance

works enables us to see how inclined toward rationalization people are and how

easily, even insidiously, they give in to it. On what grounds can any of us

tell himself that he is above this human flaw? Should I tell myself that my

mind is somehow more aesthetically and morally aware or more disciplined, and

therefore is immune to such delusions? I’m not aware of any logical grounds for

reaching that conclusion about myself or anyone else.

In fact, evidence revealing this capacity for rationalization in human

minds – some of the most brilliant of minds – litters history. How could Pierre

Duhem, the brilliant French philosopher, have written off relativity theory

because a German proposed it? (In 1905, Einstein was considered a German.) How

could Heidegger have accepted the Nazis’ propaganda? The Führer principle!

"German" science! Ezra Pound, arguably the best literary mind of his

time, propagandized on Italian radio for Fascism!

George Bernard Shaw

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

How could George Bernard Shaw or Jean-Paul Sartre have become apologists

for Stalin? So many geniuses of the academic, scientific, and artistic realms

fell into this trap. Once we understand how cognitive dissonance reduction

works, the answer is painfully obvious. Brilliant thinkers are just as

brilliant at self-comforting thinking – namely, rationalizing – as they are at

clear, critical thinking. And the most brilliant fallacious arguments they

construct – the most convincing lies they tell – are the ones they tell

themselves.

The most plausible, cautious, and responsible reasoning I can apply to

myself leads me to conclude that the ability to reason well in formal terms

guarantees nothing in the realm of practical affairs. Brilliance at formal

thinking has been just as quick to advocate for totalitarianism and tyranny as

it has for pluralism and democracy. If we want to survive, we need to work out

a moral code that counters the excesses of the human flaw called rationalization,

especially the forms found in the most intelligent people.

Rationalism is a regular precursor to intolerance. Rationalism in one

stealthy form or another has too often turned into rationalization, a dangerous

flaw of human minds. The whole design of democracy is intended to remedy, or at

least attenuate, this flaw in human thinking.

In a democracy, decisions affecting the whole community are arrived at

by a process that draws upon the carefully sifted wisdom and experience of all,

backed up by reference to observable evidence and a process of deliberate, open

decision-making. We debate. We find consensus. Then, we act. As a team.

One of the main intentions of the democratic model is to handle

subversive, secret groups. In this way, democracy simply mirrors Science. In

Science, no theory gets accepted until it has been tested repeatedly, and the

results have been peer-reviewed. There are no elites who dictate what the rest

must think. Focus is on observable evidence that all can see and then

discuss.

While some of my argument against rationalism may not be familiar to all

readers, its main conclusion is familiar to Philosophy students. It is Hume’s

conclusion. He said long ago that verbal arguments that do not begin from material

evidence, but later somehow claim to arrive at conclusions that may be applied

to the material world can be “consigned to the flames.”5 Cognitive

dissonance theory only gives modern credence to Hume’s argument.

Rationalism’s failures lead us to the conclusion that its way of

ignoring the material world or trying to impose a preconceived model on the

world doesn’t work. We can’t use Rationalism as a reliable base for a full

philosophical system. Its flaws are just too blatantly obvious. Its way of

progressing from imagined idea to idea, with little or no reference to physical

evidence, is all but guaranteed to end in rationalization instead of

rationality.

Finding a complete, life-regulating system of ideas – a moral philosophy – is far too important to our well-being for us to risk our lives on a foundational idea that historical evidence says is flawed. In order to build a universal moral code, we need to begin on a better base model of the mind.

But we’ve seen that Empiricism – a thinking system based only on sensory

impressions gathered from the material world doesn’t work either. It can’t

adequately describe the thing doing the gathering. Besides, if we lived by

Empiricism – that is, if we just gathered experiences – we would become

transfixed by what’s happening around us. At best, we would be collectors of

sense data, recording and storing bits of experience, but with no idea what to

do with these memories, how to do it, or why we would bother.

In the largest view of ourselves, we need concepts/theories in order to make decisions and act. Without mental models to guide us, we’d have no way to form plans for avoiding the same catastrophes our forebears spent so long learning (by pain) to avoid. If both Rationalism and Empiricism turn out to be shaky models on which to base a moral philosophy, then where do we turn?

The answer is complex enough to deserve a chapter of its own.

Notes

1. Elliot Aronson, The Social Animal (New York, NY:

W.H. Freeman and Company: 1980), pp. 99–106.

2. Virginia Stark-Vance and Mary Louise Dubay, 100 Questions

& Answers about Brain Tumors (Sudbury, MA:Jones and Bartlett

Publishers, 2nd edition, 2011).

3. “G.E.

Moore,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia.

Accessed April 5, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G.e._Moore.

4. “Herbert Spencer,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Accessed April 6, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Spencer.

5. David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding,

cited in Wikipedia article “Metaphysics.” Accessed April 6, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysics#British_empiricism.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.